Collection Blog

Collecting Evolutionary Ideas: Alfred Russel Wallace’s Exotic Bird Skins

January 6, 2023

In the Museum’s Natural History collection, we have over 80 bird skins collected by the naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace. A majority were collected during Wallace’s trip around Malay Archipelago between 1854-1855. A few years after Wallace’s death, these specimens were purchased from his son, William Wallace by Edward Harker Curtis in 1919 and presented to the Museum. For their age, they are in excellent condition and are still vibrant in colour.

Who Was Alfred Russel Wallace?

An explorer, collector, naturalist, geographer, anthropologist, and political commentator, Wallace was a man of many talents. He became one of the most eminent Victorian scientists.

He was born in the village of Llanbadoc, Monmouthshire on the 8th January 1823 and grew up in rural Wales and Hertfordshire. The family home was not prosperous but was rich in books, maps, and gardening activities.

At fourteen, Wallace left school and became an apprentice surveyor. As he surveyed local moors and mountains, his interest in the natural world grew. Wallace made notes and meticulous drawings of everything catching his interest.

In 1843, Wallace taught at a Leicester boys’ school. Here he met Henry Walter Bates, who encouraged him to collect butterflies and beetles. By 1845, studying plants and animals was his life’s central interest.

Bates suggested they make an expedition to the Amazon Basin in 1948. Wallace longed to test his developing ideas that living things resulted from evolution, so he invested all his savings in the expedition.

Wallace was overawed by the organisms he discovered but was not averse to killing large numbers of them. The fashion at home was to collect unusual, decorative animals and plants, and selling his fabulous collections helped fund his expeditions.

During the four years Wallace and Bates explored the Amazon, Wallace collected thousands of animals, including birds and butterflies, and made countless notes. Tragically, virtually all was lost when his ship was destroyed by fire. Undeterred to progress his evolutionary ideas, Wallace planned his own expedition to the Malaysian islands.

Wallace left Singapore in 1854. By the time he returned in 1862, he had travelled amongst remote tropical islands supporting excitingly diverse wildlife, filled countless notebooks with observations, and amassed 125,600 specimens.

While in Malaysia, Wallace wrote to Charles Darwin, asking if his observations would be of any use to him.

Wallace’s writings modestly understate his contributions to natural history. He treasured his friendship with Darwin; ‘To have inspired and retained this friendly feeling, notwithstanding our many differences in opinion, I feel to be one of the greatest honours of my life’.

Wallace retired to Dorset in 1889, he became an honorary member of the Dorset Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club in 1909, and died at his home in Broadstone on 7th November 1913.

Wallace and Evolution

Wallace’s varied experiences set him on course to become a collector of birds, insects and mammals. His expeditions to the Amazon basin, then the Malay Archipelago, enabled him to make a living, whilst contributing significantly to UK natural history collections and their scientific study. Wallace’s other personal objective was to understand why living things might change into new organisms.

Many had come to believe that the diversity of animals and plants across the continents was not fixed, but had changed gradually over time. This was called transmutation (later evolution). What was missing was any notion as to how this happened. The solution came to Wallace in a flash of inspiration early in 1858, when desperately ill with malaria.

Wallace realised that competition for resources must control both individuals’ survival and the ultimate replacement of one species by another. Small variations, observed by Wallace the collector, must underlie what he, like Darwin, called natural selection.

After recovering from the fever, Wallace wrote a paper setting out his ideas and sent it to Darwin. In 1858 this paper, and one by Darwin, were read together (by others) at a meeting of the Linnean Society.

Although Wallace argued that Darwin deserved greater credit for the natural selection concept, Wallace’s contribution was central to the theory’s construction and communication. After his return to England in 1862, Wallace became an enthusiastic proponent of ‘Darwinism’, and received many honours for his work. Fittingly, in 1908, he spoke at the 50th anniversary of the famous 1858 Linnean Society meeting.

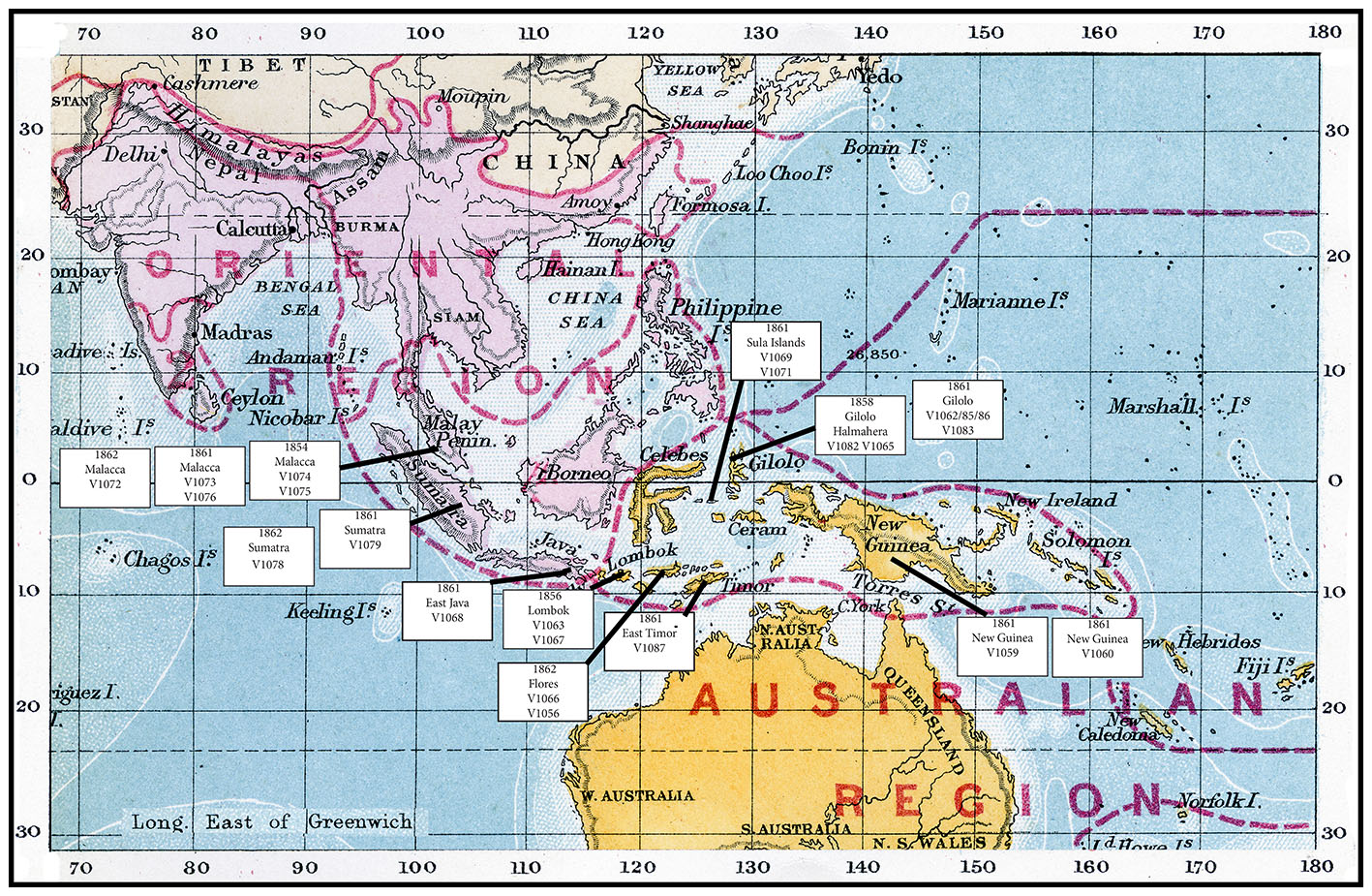

This map is taken from Wallace’s 1876 book, “The Geographical Distribution of Animals, with a study of the relations of living and extinct faunas as elucidating the past changes of the Earth’s surface”.

According to the map’s title, it is “showing the zoogeographical regions” in the straits of the Malay archipelago. The darkened line, between, … and …, was described by Wallace earlier in 1858, in a letter to Henry Walter Bates:

“In this archipelago, there are two distinct faunas rigidly circumscribed which differ as much as do those of Africa and South America and more than those of Europe and North America; yet there is nothing on the map or on the face of the islands to mark their limits. The boundary line passes between islands closer together than others belonging to the same group. I believe the western part to be a separated portion of continental Asia while the eastern part is a fragmentary prolongation of a former west Pacific continent.” In mammalia and birds, the distinction is marked by genera, families, and even orders confined to one region”.

This important boundary separating different animal groups, first recognised and interpreted by Wallace, has become popularly known as the ‘Wallace line’.

Wallace’s Conclusions about Western Man’s Arrival in “Distant Lands”

For years Wallace was a commercial collector, sending specimens back to a London agent to sell on his behalf. However, he came to realise that, in the long-term, Europeans would almost certainly have a harmful impact on the extraordinary life of the tropical forests he explored.

In his 1869 seminal book, “The Malay Archipelago”, Wallace wrote about his feelings on being given a king bird of paradise. Sadly, Wallace proved to be a true prophet.

“I knew how few Europeans had ever beheld the perfect little organism I now gazed upon, and how very imperfectly it was still known in Europe… I thought of the long ages of the past, during which the successive generations of this little creature had run their course – year by year being born, and living and dying amid these dark and gloomy woods…

“… on the other hand, should civilised man ever reach these distant lands, and bring moral, intellectual, and physical light into the recesses of these virgin forests, we may be sure that he will so disturb the nicely balanced relations of organic and inorganic nature as to cause the disappearance, and finally the extinction, of these very beings… These considerations must surely tell us that all living things were not made for man.”

Wallace and His Collecting Legacy

Why did Wallace cause the death of these birds?

It was impossible to find out about them, and classify them in any other way. Effective binoculars and photographic techniques were not available.

Presented in number, these ‘study skins’ can be unsettling. They are not mounted in familiar, life-like poses and are surrounded by natural scenes, which might make us feel more comfortable viewing them. But their lives were not taken in vain; Wallace and Darwin used their collections to research causes of variation between closely-related species. Paradoxically, studying killed animals led to our modern understanding of evolution, and helped us grasp the importance of conserving all our planet’s ecosystems.

What can we learn from museum specimens?

In the 1960s, when birds of prey that ingested pesticides laid thin-shelled eggs, museum egg collections provided invaluable information. A 100-year-old peregrine egg showed how thick the falcon shells should be. We owe it to collected birds to look after their remains, and we are still learning from them.

What did the Victorian collectors do for us?

They left us these specimens, as brightly coloured as in life. They remain objects we can appreciate scientifically and aesthetically. Also, the Victorians left us their insights and ideas that the animals inspired.

Into the 20th century, professional collectors discovered new species and sold some finds to finance further expeditions, just as Wallace did. There followed a shift to collecting living creatures for zoos, again self-funding. There is virtually no active collecting from the wild of museum specimens today, and strict international laws apply.

Wallace was one of the last great Victorians. Many of these skins were collected by Wallace himself. Looking upon them, and reflecting on their significance to evolutionary theory, we are touching history.

Jenny Cripps

Important Announcement

The lift in the Museum is currently out of action.

We hope to resolve this very soon and apologies for the inconvenience.