Collection Blog

Fordington St. George by H. J. Moule

April 22, 2023

From the ‘Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society’ Volume 5, 1844, an article written by Henry. Joseph. Moule, M.A. entitled ‘Fordington St. George’

As it is a short paper that has been asked for, and a paper not so much on the church, as on a -particular feature of the church of Fordington St. George, general remarks shall be as brief as may be.

The site of the church was well chosen. It stands on the highest spot in the village. Yet the site was oddly chosen too. The church was set down in a great Romano-British Cemetery. The growth of a graveyard round a church is, of course, universal almost, and natural. The erection of a newly founded church in an old graveyard is uncommon, I take it.

On approaching the church you pass three good, plain, massive, 17th-century altar-like tombs; one of them bearing the well-known solemn epitaph, beginning

“Remember that Death tarrieth not.” (Remember that Death tarryeth not, and that the Covenant of the grave is not showed unto thee. For I was as thou art, and thou shalt be as I am.)

The Tower is worth noticing, not only as being a capital one in design, colour and position but as having what, as far as I know, is a peculiarity of the plan. It’s north and south faces are each 1ft. 4in. narrower than those on the east and west. Of its six bells the third and fifth are mediaeval, Legends: –

“Sancta Katarina ora pro nobis;” and “In multis annis resones campan Johannis.”

These bells are said to be those, or some of those, referred to in the doggerel couplet still current in Wool and elsewhere:-

“Wool streams and Combe wells –

Fordington rogues stole Bindon bells.”

The cage is probably the original one.

Readers of the third edition of Hutchins may be led to think that my honoured father, the late Vicar, was answerable for the dreadful design of the north aisle. I take this opportunity of denying it. A then leading architect in the Diocese recommended the design, which doubtless is worse than any journeyman mason in the county could now be guilty of. On the other hand my father first reduced and then removed the western gallery, which he found actually so high that there were hat pegs on the crown of the tower arch. And he revealed to sight several curious bits in the Church.

Well, this North Aisle exists. The eighteenth-century Chancel exists, in place of a glorious one with a timber roof, stalls, and rood loft. The Nave and Transept are ceiled. The interior is spoilt as a whole. Still, it possesses several interesting detached features. I can but simply name the plain stone Elizabethan pulpit, the rood loft staircase, the curious little window high up in the Transept, and the piece of encaustic pavement in situ, but with the patterns quite gone. In my boyhood, by the way, these patterns were still so far remaining that I managed to make them out and depict them. Close to this pavement is laid down a number of tiles which were found under pews. Several of these tiles are of some interest. Not a few of them have the Fylfot cross.

Besides the above bits there is an interesting remnant of a piscina and arch in the Transept, and two (perhaps three) Norman piers, one with a cap of apparently later date; and carrying singularly rude pointed arches.

I now come to the two really noteworthy features in St. George’s, both .at the South door, and both preserved from an older church and enshrined by the 15th-century builders in their own work, more so. Indeed it may be noted that here they seem to have been so disposed to an even uncommon degree. This appears from their retaining the Norman piers, although fitting in very awkwardly.

The first of the said features is the Holy Water Stoup. Its font-like shape is remarkable, but by no means unique. There is a much later one, for instance, at Hastings. But, as far as my limited knowledge goes, the moveable, or moveable-looking arrangement of this one at St. George’s is peculiar. It was hidden behind a high pew and forgotten until uncovered by my father ‘some thirty-five years ago. The slight moulding and ornament on it are perhaps hardly enough to settle its date. But I take it to be Norman. Piscinae of that date, and with something of a family likeness exist, I believe, in several places; at Bosharn among others. But these, it seems, resemble short, fixed columns, with the cap hollowed; and are not, as this Stoup is, like a minute font.

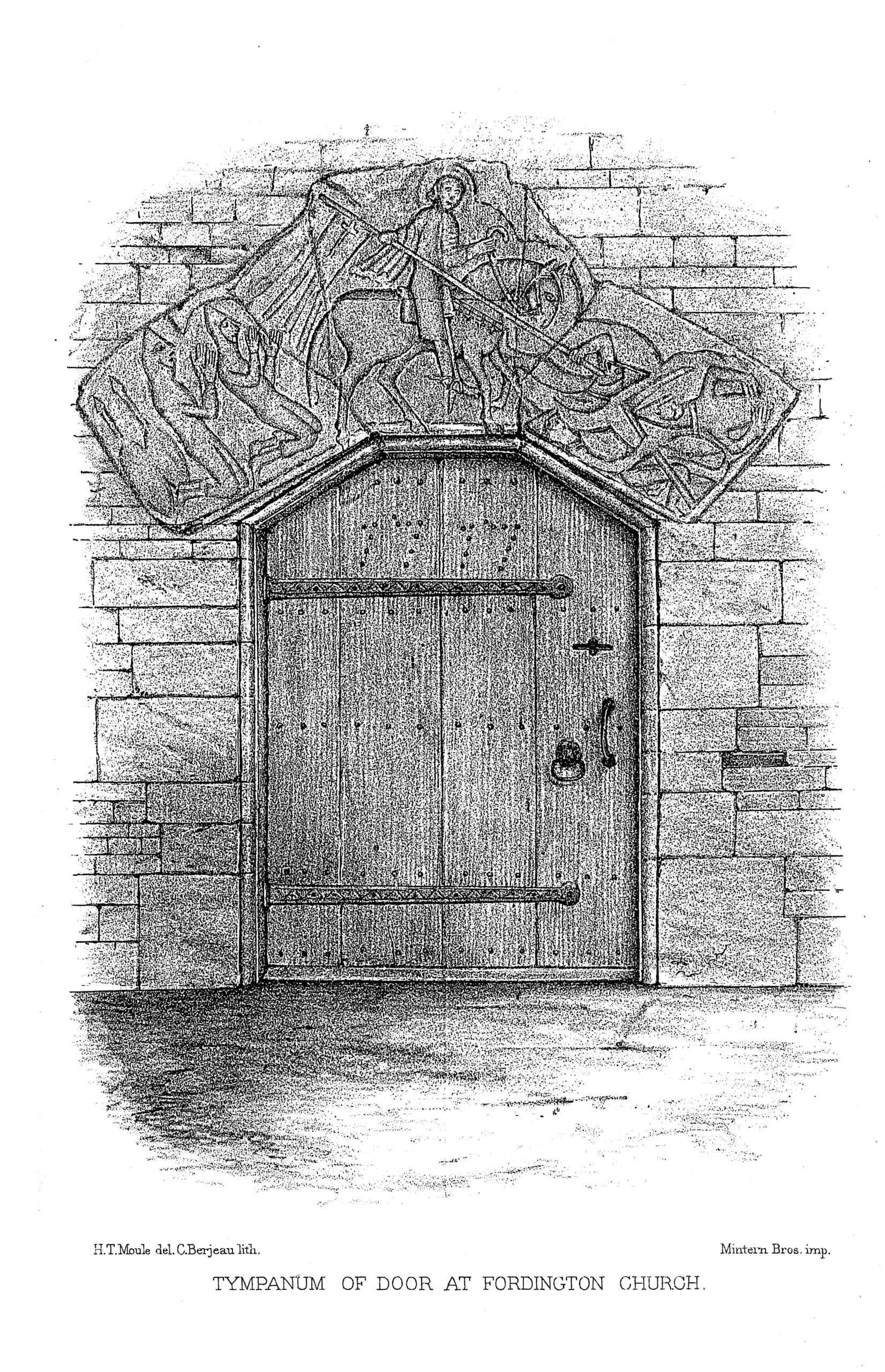

I must now pass on to the Tympanum, close to the Stoup, but outside of instead of within the South door. A Tympanum within the South door of Tarrant Rushton Church may be noticed in passing. It is like this one in date, and to a certain extent in shape, but quite different in subject, and also in construction, as far as I can judge from the rough cut in Hutchins.

I may as well at once express my belief, for what it is worth, that this Fordington Tympanum is undoubtedly Norman. I do not forget that at the meeting of the Archaeological Association in 1871, an opinion that it is much more recent was very decidedly expressed. It was said that the hardness of the stone accounts for the character of the carving. I doubt the fact and deny the inference. As to the stone, there is a theory that it is of foreign, even of oriental origin. I can find no foundation for this idea. It is a more prevailing, and much more likely belief, that it is of Portesham Oölite. At the same time there is a tradition at Sutton Pointz that of stone from the now grass-grown quarries on Loddun, a hill there, all the “Wold arnshunt builduns to Darchester “ were constructed. “There,” said my informant, ”Portland line – he weren’t finished – not then.” But, whether from. Portesham or Loddun, I think I shall be borne out in believing that oölite from those places, as from Portland, is not when first quarried of by any means stubborn quality. But if it were as hard as basalt, what then? Would the iron hardness of the stone have made the post-Norman carver plainly, if rudely, portray the Norman nasal, the Norman hauberk, the Norman shield, the Norman prick-spur? For in truth, this carving might be the petrifaction of some lost bit of the Bayeux Tapestry. Every feature, almost, in the Tympanum may be clearly traced in the tapestry. Almost, for from my remembrance of the latter, and examination of the imperfect set of the facsimiles thereof to which alone I have access here, I cannot satisfy myself that the strapping of the shield to the neck, so conspicuous in the Tympanum (luke’s “Ecclesiastical Art,” p. 2420, shown in the tapestry. The object below the horseman’s foot I have always thought to be the end of his sword hanging, of course, on the near side of the horse. I think so still, yet in the Tapestry I see a different object so hanging, which may be a large dagger or a long end of the girth. This, whether dagger or girth, maybe the thing of which the Norman carver here was thinking – just possibly.

As to the subject, I have no new theory to offer. Abroad – and the Anglo-Norman was in much harmony of thought with the Franco-Norman, with the Frenchman, and with the German – abroad, the Tympanum mostly displays some figure or symbol of Our Lord, as by the way we see on the Tarrant example. But here at Fordington it is not Our Lord who is figured or symbolized. His cross, indeed, is fully shown, but not Himself. Yet, the horseman, though not divine, is sainted. His aureole, however faint and rude, is plain enough. Now this is St. George’s Church. About two years before one of the dates assigned for its founding St. George was beheld (men said) charging the Paynim. I see no better likelihood than the old accepted one that this rider is St. George in the onslaught at Antioch. It may be objected that the enemy is in Norman harness. This is nothing. Everyone knows that variation of costume, &o., owing to either differing time or clime, was constantly ignored in mediaeval, nay, down to modern times. Many here must have seen the immortal coloured print of the Prodigal Son going away from home in a post chaise.

I have called this rudely carvel door-head a Tympanum. The books call it so. It is well. But I would in one-word point out that it is a widely different feature from the normal Tympanum; and is uncommon – I had almost said unique. The regular Tympanum, of constant occurrence, especially abroad, is a massive lintel stone, fitting into the soffit of an arch above it. With the soffit, it is, in truth, like half of a tambourine, τύμπαυου. This Tympanum here is not a stone – it is six stones. It is not a lintel – it is an arch, however rude.

I conclude by pointing out that there are faint traces of red paint on the stone, and recording that the whole was hidden in plaster and unknown until discovered by Clerk Brooks, whom I well remember.

Important Announcement

The lift in the Museum is currently out of action.

We hope to resolve this very soon and apologies for the inconvenience.