Collection Blog

Some Romano-British Relics found at Max Gate, Dorchester by Thomas Hardy

July 18, 2022

The following article entitled ‘Some Romano-British Relics found at Max Gate, Dorchester’ by Thomas Hardy is from the ‘Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society’, volume 11 published 1890.

“I have been asked to give an account of a few relics of antiquity lately uncovered in digging the foundations of a house at Max Gate, in Fordington Field. But, as the subject of archaeology is one to a great extent foreign to my experience, my sole right to speak upon it at all, in the presence of the professed antiquarians around, lies in the fact that I am one of the only two persons who saw most of the remains in situ, just as they were laid bare, and before they were lifted up from their rest of, I suppose, fifteen hundred years. Such brief notes as I have made can be given in a few words. Leaving the town by the south-eastern or Wareham Road we come first, as I need hardly observe, to the site of the presumably great Romano-British cemetery upon Fordington Hill. Proceeding along this road to a further distance of half a mile, we reach the spot on which the relics lay. It is about fifty yards back from the roadside, and practically a level, bearing no immediate evidence that the natural contour of the surface has ever been disturbed more deeply than by the plough.

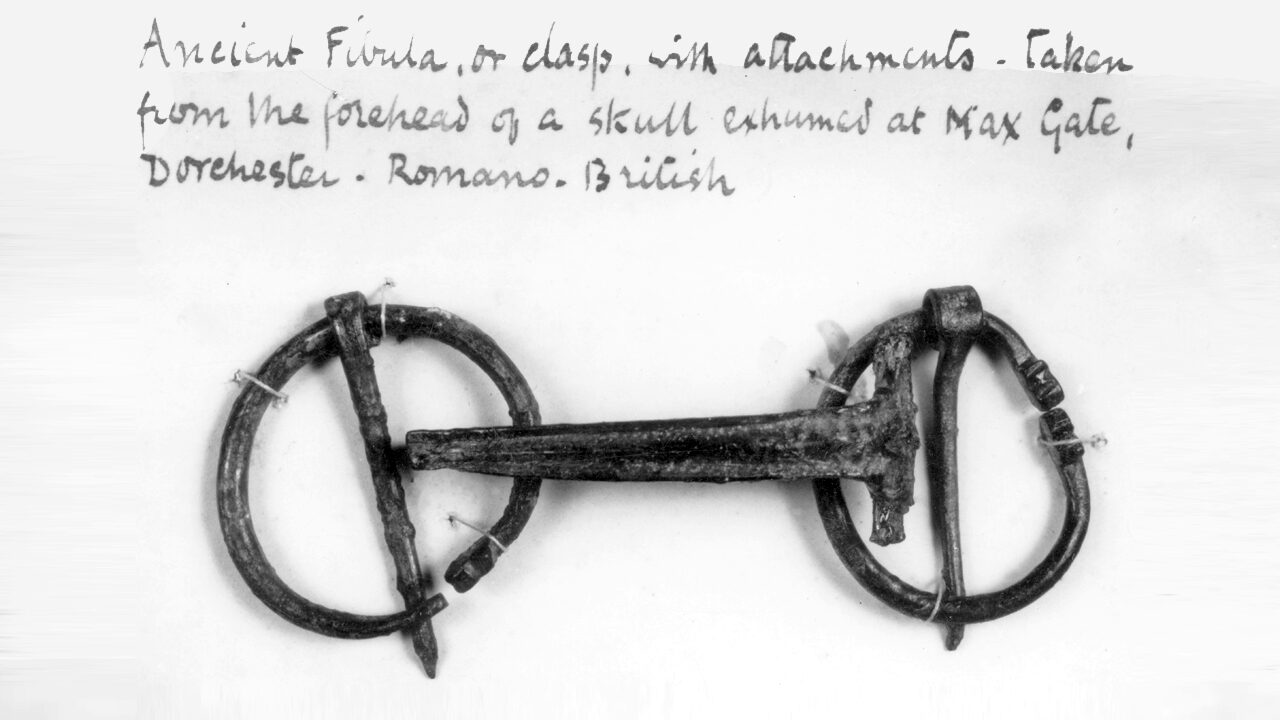

But though no barrow or other eminence rises there it should, perhaps, be remarked that about three hundred yards due east from the spot stands the fine and commanding tumulus called Conquer Barrow (the name of which, by the way, seems to be a corruption of some earlier word). On this comparatively level ground, we discovered, about three feet below the surface, three human skeletons in separate and distinct graves. Each grave was, as nearly as possible, an ellipse in plan, about 4ft. long and 2½ ft. wide, cut vertically into the solid chalk. The remains bore marks of careful interment. In two of the graves, and, I believe, in the third, a body lay on its right side, the knees being drawn up to the chest, and the arms extended straight downwards, so that the hands rested against the ankles. Each body was fitted with, one may almost say, perfect accuracy into the oval hole, the crown of the head touching the maiden chalk at one end and the toes at the other, the tight-fitting situation being strongly suggestive of the chicken in the eggshell. The closest examination failed to detect any enclosure for the remains, and the natural inference was that save their possible cerements, they were deposited bare in the earth. On the head of one of these, between the top of the forehead and the crown, rested a fibula or clasp of bronze and iron, the front having apparently been gilt. This is, I believe, a somewhat unusual position for this kind of fastening, which seemed to have sustained a fillet for the hair.

In the second grave a similar one was found, but as it was taken away without my knowledge I am unable to give its exact position when unearthed. In the third grave nothing of the sort was discovered after a careful search.

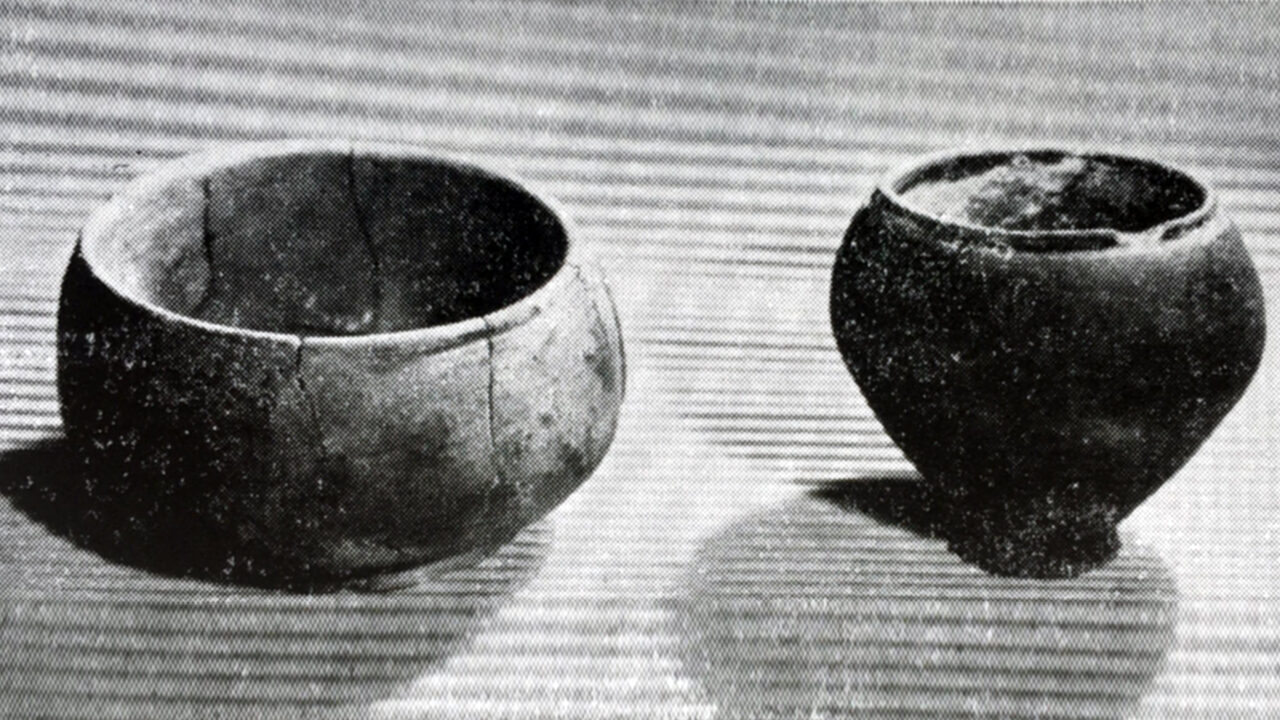

In the first grave a bottle of white clay, nearly globular, with a handle, stood close to the breast of the skeleton, the interior being stained as if by some dark liquid. The bottle, unfortunately, fell into fragments on attempting to remove it. In the same cavity, touching the shin bones of the occupant, were two urns of the material known as grey ware, and of a design commonly supposed to be characteristic of Roman work of the third or fourth century. It is somewhat remarkable that beside them was half, and only a half, a third urn, with a filmy substance like black cobweb adhering to the inner surface.

In the second cavity were four urns, standing nearly upright like the others, two being of ordinary size, and two quite small. They stood touching each other, and close to the breast of the skeleton; these, like the former, were empty, except of the chalk which had settled into them by lapse of time; moreover, the unstained white chalk being in immediate contact with the inner surface of the vessels was nearly a proof that nothing solid had originally intervened. In the third grave, two other urns of like description were disclosed.

Two yards south from these graves a circular hole in the native chalk was uncovered, measuring about two feet in diameter and five feet deep. At the bottom was a small flagstone; above this was the horn, apparently of a bull, together with teeth and bones of the same animal. The horn was stumpy and curved, altogether much after the modern shorthorn type, and it has been conjectured that the remains were possibly those of the wild ox formerly inhabiting this island. Pieces of a black bituminous substance were mixed in with these, and also numerous flints, forming a packing to the whole. A few pieces of tile, and brick of the thin Roman kind, with some fragments of iridescent glass, were also found about the spot.

There was naturally no systematic orientation in the interments —the head in one case being westward, in the other eastward, and in the third, I believe, south-west. It should be mentioned that the surface soil has been cleared away to a distance extending 50ft. south and west from where these remains were disinterred, but no further graves or cavities have been uncovered — the natural chalk lying level and compact — which seems to signify that the site was no portion of a regular Golgotha, but an isolated resting-place reserved to a family, set, or staff; such outlying tombs having been common along the roadsides near towns in those far-off days—a humble Colonial imitation, possibly, of the system of sepulture along the Appian Way.

In spite of the numerous vestiges that have been discovered from time to time of the Roman city which formerly stood on the site of modern Dorchester, and which are still being unearthed daily by our local Schliemann (Edward Cunnington) one is struck with the fact that little has been done towards piecing together and reconstructing these evidence into an unmutilated whole—such as has been done, for instance, with the evidence of Pompeian life — a whole which should represent Dorchester in particular and not merely the general character of a Roman station in this country — composing a true picture by which the uninformed could mentally realise the ancient scene with some completeness.

It would be a worthy attempt to rehabilitate, on paper, the living Durnovaria of fourteen or fifteen hundred years ago—as it actually appeared to the eyes of the then Dorchester men and women, under the rays of the same morning and evening sun which rises and sets over it now. Standing, for instance, on the elevated ground near where the South-Western Station is at present, or at the top of Slyer’s Lane, or at any other commanding point, we may ask what kind of object did Dorchester then form in the summer landscape as viewed from such a point; where stood the large buildings, were they small, how did the roofs group themselves, what were the gardens like, if any, what social character had the streets, what were the customary noises, what sort of exterior was exhibited by these hybrid Romano-British people, apart from the soldiery? Were the passengers up and down the ways few in number, or did they ever form a busy throng such as we now see on a market day? These are merely the curious questions of an outsider to initiated students of the period. When we consider the vagueness of our mental answers to such inquiries as the above, we perceive that much is still left of this fascinating investigation which may well occupy the attention of the Club in future days.”

Important Announcement

The lift in the Museum is currently out of action.

We hope to resolve this very soon and apologies for the inconvenience.